Like many people who grew up on Tyneside, my first memories of the Great North Museum: Hancock (then the Hancock Museum) came as a child. For me, however, the most enduring memory is that of standing outside the museum. From the age of eight I waited each day at the bus stop outside the museum to get the bus home – that bus stop of course no longer exists as it was bulldozed along with the old formal entrance to the museum, in the creation of Newcastle’s central motorway.

The next set of memories come as a young museum professional in the 1980s attending meetings on the very uncomfortable wooden benches in the old museum lecture theatre but also being taken on tour into the amazing stores of the museum to view not only collections of huge scientific value amassed over a 200 year period but also specimens provided by zoos and other sources and stored in freezers awaiting the expert attention of the museum’s well known taxidermist Eric Morton.

But of course the collections of the Great North Museum: Hancock are not only the collections of the Hancock Museum. As an archaeology undergraduate (at Leicester University) in 1980 I chose to do my undergraduate dissertation on Neolithic and early Bronze Age jet ornaments from the North East of England and the spacer plate necklace and V-pierced button specimens from the Museum of Antiquities were a rich source of material for that dissertation. Many hours were spent photographing and drawing objects from the Museum’s fantastic collection.

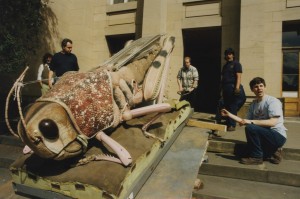

Some monster creepy crawlies entering the museum for an exhibition in 1995. Eric Morton, taxidermist, can be seen at the far left.

I returned to the Hancock Museum, as was, in 2001 as the grandly titled Senior Curator. As a non-natural scientist, who didn’t even have a biology O level it seemed rather a cheek to be the senior curator of the Hancock. However, I have been lucky enough across my life in museums, libraries and archives to have run a wide variety of organisations covering, I think, almost the whole world of human knowledge!

Supported by an excellent team with the subject specific knowledge I quickly confirmed that I wasn’t suddenly going to become an expert Paleo-ethno botanist but that my general leadership and management skills would be applied to help develop the Hancock and that I would ensure that I had enough knowledge to converse about the collections with the public and with specialists as required.

2001 was an exciting time to arrive at the Hancock. The business model at the time was very much oriented to blockbuster exhibitions either brought in or self-generated and many people will remember the thick black cloth covering the ceiling of the first gallery in the Museum where many of these exhibitions were staged. People will also remember the tradition of throwing, from above, coins onto this cloth which were periodically raked off and added to the Museum’s donations.

The first exhibition I was involved with however brought a particular challenge. An exhibition on the science of Star Trek looking at which elements of the Star Trek technology were possible and which (at least according to Einsteinian physics!) were impossible. Unfortunately the exhibition had been hired in in US dollars and at about this time the pound suddenly fell against the US dollar, significantly increasing the cost to us of the exhibition and increasing our funding challenge for that year.

The most exciting thing however coming up was the bid from Newcastle Gateshead to be Capital of Culture and the energy associated with this bid linked with a strong desire from Newcastle University to strengthen local and regional relationships provided the perfect opportunity to address some of the challenges which the Hancock faced.