By Bill Griffiths, Head of Programmes and Collections

20 years ago this month, we opened Segedunum Roman Fort, Baths and Museum to the public. It’s a cliché – but to me it feels like yesterday!

At the time of its opening, I was newly in post as the Museum’s Curator, having been the on-site Archaeology Project Officer right through its development. We had been working for three and a half years on the project since receiving funding from, among others, the Heritage Lottery Fund, and I had been involved for about two years before that working for Paul Bidwell on the initial feasibility study for the site.

The opening was a big deal. We had a couple of preview days for the families of people involved in the project including from the museum service, North Tyneside Council, and the contractors – and I remember putting them through a fire alarm just so we could test the system!

That week also saw a lot of local TV coverage, which you don’t get so much of these days. I particularly remember a local TV news presenter doing a piece from the bath-house. The final shot was a bit Monty Python as he stripped off and took a bath – showing his naked backside on camera – and this was the early evening news, hours before the evening watershed!

The day before we opened to the public, the car park was covered in a huge marquee for the VIP launch. I had been rushing around getting all sorts of things ready – and in my memory I suddenly heard our then Director David Fleming introducing me to say a few words. I don’t recall having a speech ready!

Opening day itself saw the famous Roman re-enactment group, the Ermine Street Guard, march from Wallsend Metro station, where we had a Metro train decked out as a massive advert for the Museum, down to the site, where we had a queue of eager visitors awaiting the opening moment. They presented a ceremony alongside members of Cohors Quinta Gallorum, our own re-enactment group based at Arbeia.

As I recall, the first day went well and the public were none the wiser about just how frantic things were behind the scenes.

In the original plan, the builders were meant to finish the Museum six weeks before opening. We were to recruit the staff team at that point and have them in place for about a month’s training before we opened to the public. In the event, the builders did not fully finish on site until part way through opening day itself! We were actually trained on how to set the intruder alarm on the afternoon of the first day. Geoff Woodward (now the Museum Manager for North and South Tyneside, but then Customer Services Officer for Segedunum and about three weeks in post) and I sat with the builders that afternoon for about an hour as they handed the keys to the building over to us – one by one.

The next few weeks passed in a blur as Geoff and I and the team started to learn how to operate the building. My overarching memory is of colleagues from across TWAM coming down and helping us learn the systems needed to run a museum, from conservation requirements to cash-handling, to accepting objects from members of the public. On top of that, and I am really showing my age here, email was another brand new thing we had to learn!

After all those years working on the project, it was a great relief to find that the public loved the Museum too. I recall that analysis of the visitor’s comments book identified over 20 different spellings of the word ‘excellent’. 20 years on, I still cannot argue with that.

It’s easy to forget how significant Segedunum is for its archaeology. It is the most excavated fort on Hadrian’s Wall, and the first place to see Roman Cavalry barracks fully excavated. Since Segedunum’s opening, the extra mural bath-house has been rediscovered by the Wallquest community archaeology project and additional funding has allowed the completion of the section of Hadrian’s Wall that lies within the Museum’s grounds. These tell an incredible story of several phases of collapse and rebuild, as well as containing outstanding evidence for the function of the water supply system in Roman times. And of course, its not just Roman; the Wallsend B pit excavation won an award from the Association for Industrial Archaeology.

Today, 20 years on, Segedunum stands proud, not only as a celebration of Hadrian’s Wall and the Frontiers of the Roman Empire World Heritage Site, but with its displays of the mine and shipyard, it is also a testament to the place Wallsend occupies in history. Segedunum has become a source of pride for the town’s past and an inspiration for its future.

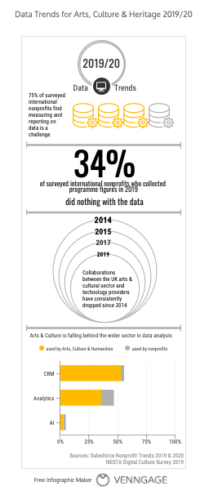

As a charity, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums rely on donations to provide the services that we do and our closure, whilst necessary, has significantly impacted our income. Please, if you are able, help us help us continue to inspire people through arts, culture and heritage in the North East by donating by text today. Text TWAM 3 to give £3, TWAM 5 to give £5 or TWAM 10 to give £10 to 70085. Texts cost your donation plus one standard message rate. Thank you.