Working for a museum and working with their natural history collections is something that I have wanted to do since I left university. I did wander through the bird galleries of the old Hancock museum as a girl and marvel at the different animals that existed in the world. (Not that every species was displayed as there are millions.) I loved the sounds and smells of the old building. Studying Zoology, I spent most of my fourth year taking lectures in the university museum at Dundee which was essentially a room with some natural history objects in old cases located around the room’s perimeter. I loved looking at the skulls and deducing which animal they came from.

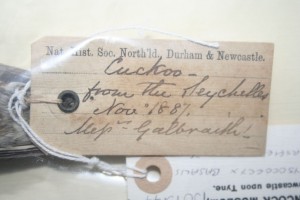

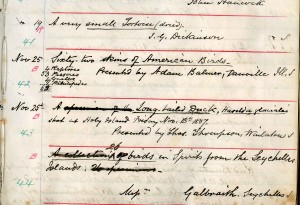

The Great North Museum: Hancock holds a vast number of objects that range from the insects and beetles to the large bird and animal mounts. There are skeletons and taxidermied specimens, specimens preserved in alcohol, and specimens stored as skins. There are also fossils of animals that lived in the region in prehistoric times. All of these specimens need to be cared for and look after for future generations.

Some of the objects in the collection were prepared by the great taxidermists of their time, such as John Hancock, whom the original museum was named after. Also, mammal and bird mounts were prepared by Roland Ward who was an important taxidermist in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. All of the objects are a record of the species that existed at a particular location at a particular point in time. Museums hold examples of species that have become extinct or endangered in modern times.

Working with the collections has allowed me to get very close to some of the objects, including the time when we packed up the whole museum during the redevelopment. In the past I was charged with the job of checking the condition of the mounts that we used to keep in our “Abel’s Ark” display. This involved checking for signs of pests such as moths and cleaning the specimens. In this display we had a number of deer, a Colobus monkey and a red panda, as well as a polar bear and a male lion. How many jobs allow you to get that close to an actual lion? Most of the animals that were in Abel’s Ark are now found in the “Living Planet” gallery.

During my museum career I have been able to meet with groups such as NatSCA who are the Natural Sciences Collections Association. These are like minded people who work in museums who come together to discuss issues within the museums service. They are also a brilliant group to know because all of the members come from most institutions around the country, so if you need some help or advice with a natural history related issue they can usually help. Their website is a great way of accessing information about the group and seeing what events they have coming up. We are having the next NatSCA AGM at the Great North Museum: Hancock next May.

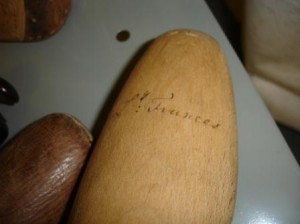

One of my favourite collections at the Great North Museum: Hancock has to be the Osteology collection. The bones of the skeletons all have a specific function, and their form is so precise to allow the animal to move in the exact way it has to in order to survive in its habitat. I find this amazing.